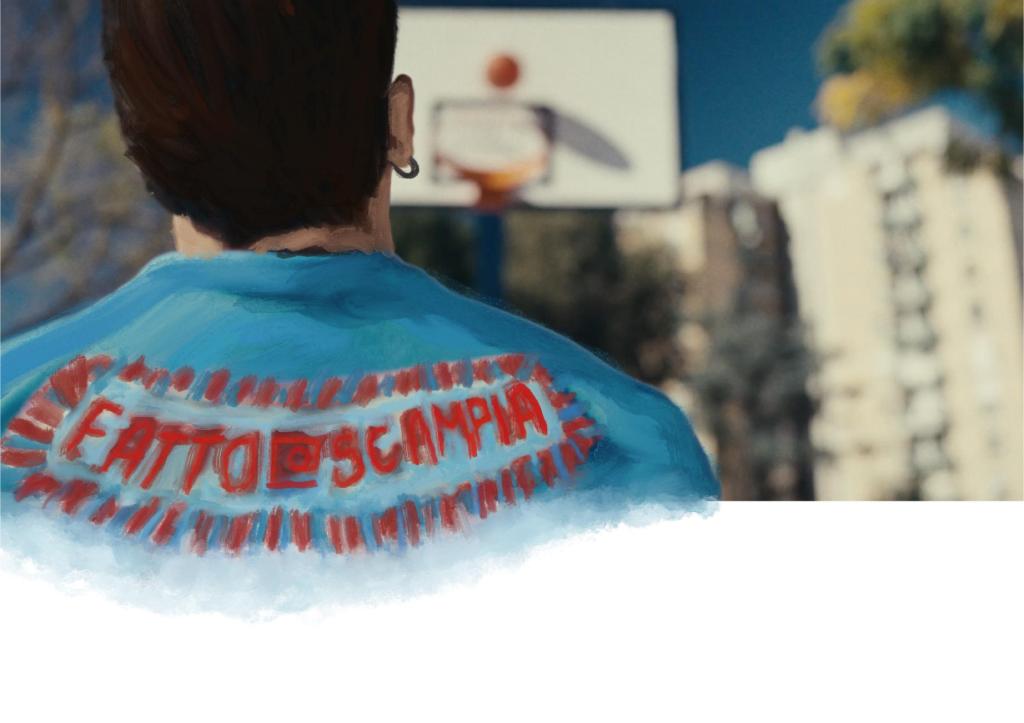

Welcome to this thought-provoking conversation about one of the most interest projects, “A Sewing Machine of One’s Own,” developed by the talented duo of Eleonora Cecere and Andrea Bertello. Both PhD candidates in Design for Made in Italy, Eleonora and Andrea bring a wealth of creative vision and scholarly research to their work. I had the distinct pleasure of meeting them at the FASHIONCLASH Festival 2025, held in November in Maastricht, the Netherlands, where they showcased their promising initiative in collaboration with the social sewing workshop Fatto a Scampia.

“A Sewing Machine of One’s Own” is a deep research and co-creation project that finds its heart within the Fatto a Scampia social sewing workshop. This initiative represents a landmark exploration of fashion as a multifunctional tool—cultural, political, and communal. Eleonora and Andrea’s project seeks to delve deep into the potential of fashion not just as an aesthetic venture but as a powerful means of empowerment, education, and symbolic resistance. This aligns seamlessly with the objectives of the 17th edition of the Fashion Clash Festival, which aims to spotlight creatives committed to collaboration, activism, and community co-creation.

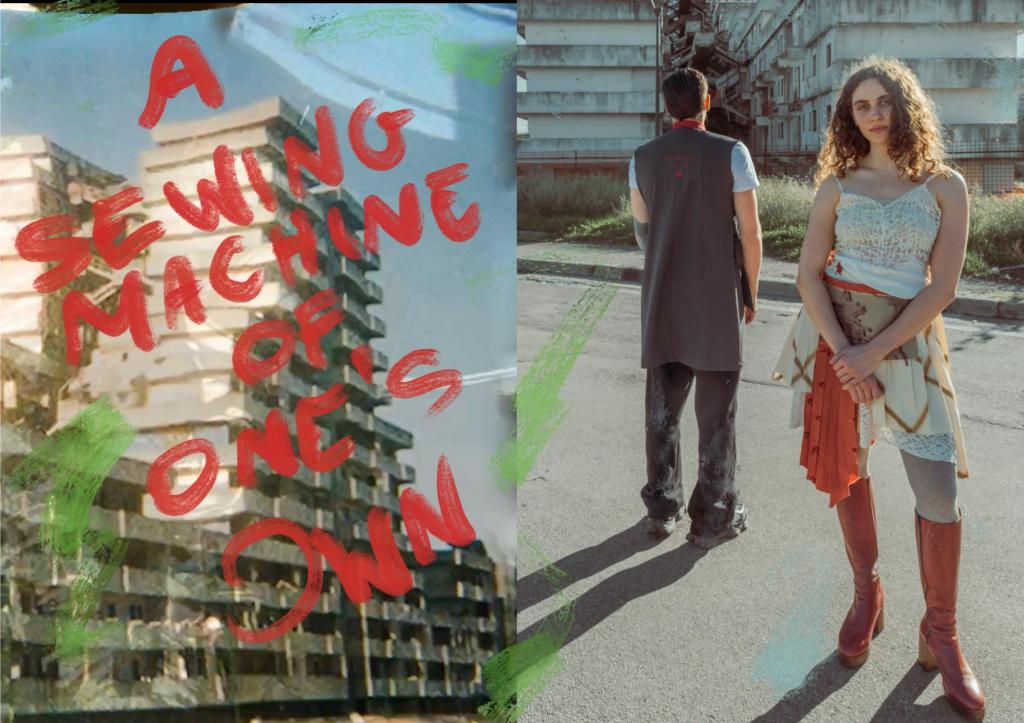

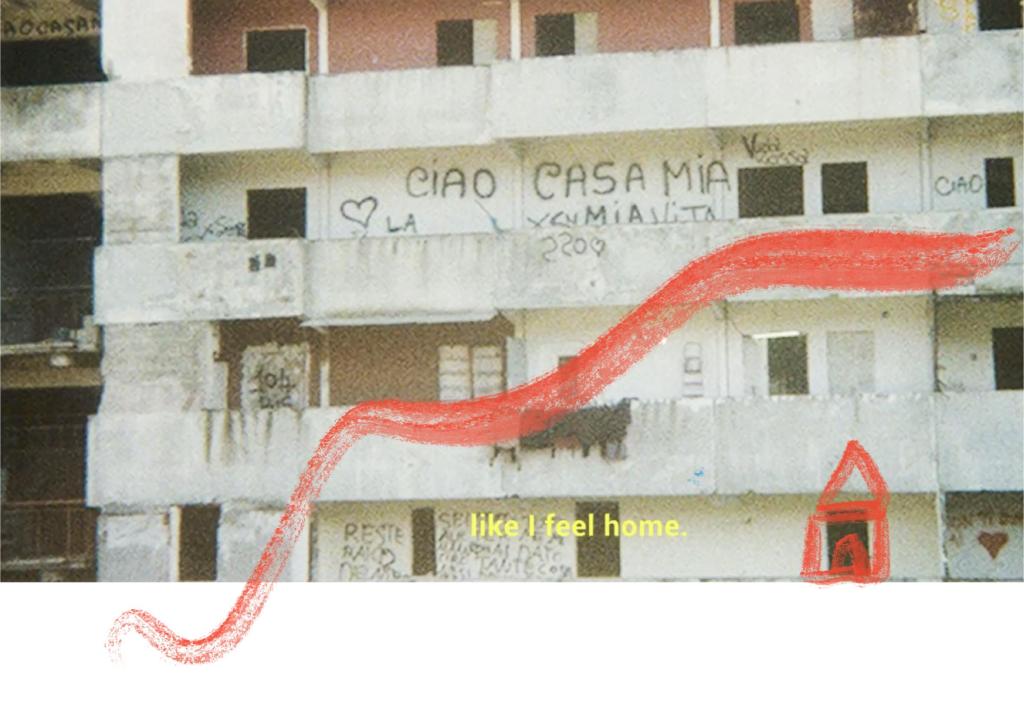

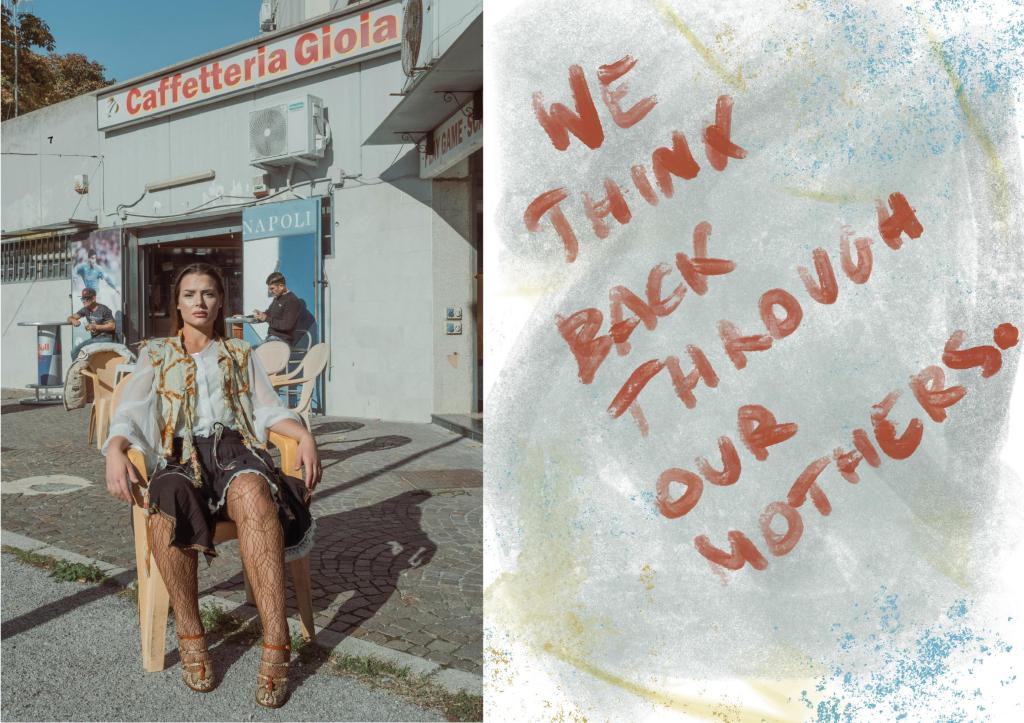

The backdrop of Scampia is significant; it is a neighborhood often misrepresented in mainstream narratives. Through this project, Eleonora and Andrea make us to reflect on a different story—one that reveals a deep background made by skills, aspirations, and possibilities. By collaborating intimately with local communities, they transform the negative perceptions associated with the area into a story of hope and powerful change. The project encourages us to consider how fashion can be a vehicle for social change, allowing individuals within marginalized communities to express their identities and reclaim their narratives.

The title of the project itself draws inspiration from the powerful words of Virginia Woolf, who famously encouraged women to claim “a room of one’s own.” For Eleonora and Andrea, this personal space manifests as a sewing machine—a metaphorical tool representing autonomy, identity development, and self-determination. By equipping participants with the skills and tools of fashion design, Eleonora and Andrea empower them to express their stories, dreams, and individuality.

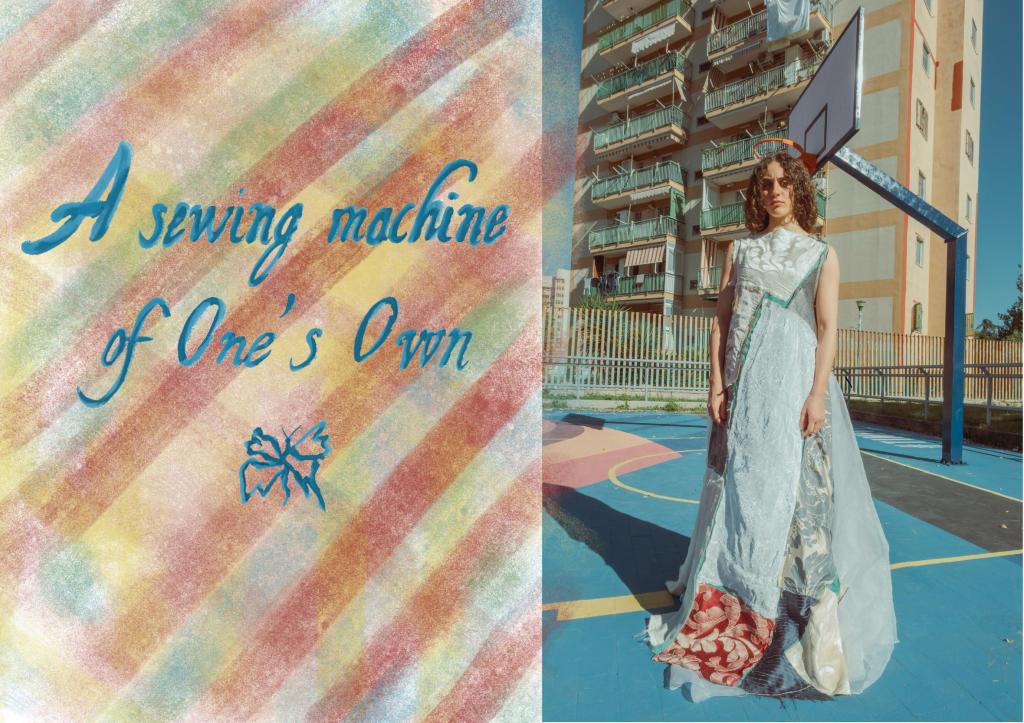

Collaboration with Fatto a Scampia has taken on an educational dimension, where seamstresses, volunteers, and local youth have been actively involved in every stage of creating a capsule collection. This collection, comprising ten unique garments, reflects a synthesis of technical skills, personal stories, and the local aesthetic. Rather than framing the project around the final product, Eleonora and Andrea emphasize the collaborative process at its heart. This model of co-design not only enhances capabilities but also promotes up-skilling and re-skilling, fostering a sense of ownership and pride among the participants.

Today, it is imperative to include and collaborate with realities like Fatto a Scampia. As the industry grapples with issues of sustainability, ethical practices, and the need for greater inclusivity, initiatives like “A Sewing Machine of One’s Own” highlight the significance of grounding fashion in real-world contexts. By collaborating with local communities, designers can gain invaluable insights that challenge dominant paradigms, allowing for a more authentic and representative approach to fashion. This collaboration becomes an act of resistance against the fast-fashion model, redefining creativity as a communal practice that nurtures both individuals and communities.

This project raises critical questions about the role of designers in contemporary society. In a climate where the fashion industry risks losing its relevance, Eleonora and Andrea’s approach transforms collaboration into a political act, restoring meaning and humanity to the design process. “A Sewing Machine of One’s Own” advocates for a creative practice that celebrates communal efforts, turning fragility into resilience and limitations into resources.

In the below interview, Eleonora and Andrea will share their insights on how their project reflects new paradigms in fashion. We’ll explore the importance of ethical practices, the interweaving of diverse narratives, and the potential for collective regeneration within the industry. Their inspiring work reinforces the notion that fashion can be a powerful catalyst for social change, personal empowerment, and community revitalization. Together, they embody the spirit of a new generation of designers dedicated to making fashion more inclusive, ethical, and closely aligned with the communities they serve:

What significance does the project “A sewing machine of one’s own” hold in the broader context of fashion’s role in supporting marginalized communities, particularly in Scampia?

A Sewing Machine of One’s Own is an experimental project born inside Fatto a Scampia, a social tailoring atelier that supports local women through concrete pathways of professional training and job placement. Many of these women face harsh, systemic obstacles, including school dropout, economic precarity, and the difficulty of accessing stable employment within the context they live in.

For this reason, the project placed people, their vision, their capabilities, at the center. The seamstresses and volunteers played an essential role in every phase of the process, not as executors but as co-authors. The project cannot be understood solely through the lens of the capsule collection, its deepest value lies in the process itself, in the educational model we experimented with together for the first time.

We believe in fashion’s potential as a tool capable of expressing identity while also revealing the social and urban narratives that have defined this territory for the past forty years, as well as the ongoing struggles it continues to face. As fashion designers, we worked to bring out, through dialogue with the youngest women in the atelier, the aesthetic elements that truly belong to Scampia. We gathered them, reframed them, and decontextualized them, transforming them into materials for research and innovation.

How does the collaboration between you ( Andrea Bertello and Eleonora Cecere ) highlight the potential of fashion as a means of empowerment and resilience for women facing socio-economic challenges?

Today, it is increasingly urgent to rethink fashion as a tool in service of disadvantaged communities. In our vision, fashion’s aesthetic codes can become instruments of advocacy, but they do not have to endlessly reproduce a stereotyped or fossilized image of what Scampia has endured for decades.

On the contrary, the elements we brought into the collection carry a momentum for change. They are a way of saying that renewal starts from what already exists, from a deep understanding of the place where one lives, from recognizing why certain narratives need to be overturned or reclaimed to open up new possibilities.

Sharing the tools of design was fundamental, it made possible the co-creation of a capsule collection of around ten pieces with the seamstresses of Fatto a Scampia, enhancing territorial identity and activating processes of inclusion and creative training. From this work emerged new opportunities for experimentation, dialogue, and collective growth, not only for them but also for us.

In what ways did the Fashion Clash Festival’s criteria for selecting creatives emphasize the necessity of community engagement and activism in fashion, and why is this approach crucial at this moment?

This year, the selection criteria of the Fashion Clash Festival highlighted a very clear direction: to choose creatives and projects capable of activating real communities, of working with people rather than merely on them, and of placing at the center an idea of fashion as a cultural, social, and political tool. As we said, today fashion risks losing relevance precisely because it does not engage enough with the reality we live in. We view this discipline on the same level as other arts: a field capable of imagining scenarios, yes, but also of building something tangible and necessary. Proposing ethical and sustainable fashion, including from a social perspective, should be considered a new form of avant-garde, even though bridging the world of social initiatives with the more polished fashion system is no easy task.

In his post-Fashion Clash review, Philippe Pourhashemi emphasizes the historical moment we are in: in a sector in crisis, with an evident backlash and real exhaustion, we need voices that bring compassion, generosity, and support back to the center. The more fashion becomes dehumanized, the more necessary it is to work as a team, to unite and develop ideas and projects together. This is exactly the heart of our project: A Sewing Machine of One’s Ownwas born from co-design, from a collective effort that rejects the isolated designer and revives the idea of shared creativity. The team is not a frame, but the engine through which we transform fragility, limits, and obstacles into resources; resilience thus becomes a daily practice and a founding principle of our research.

In this sense, Fashion Clash offers a space where the needs and possibilities of a paradigm shift emerge strongly: bringing the community back to the center, placing people and collaborative processes at the heart of creative work, and imagining a way of making fashion that is more human and conscious. It is not an absolute definition, but a powerful indication: a place where these possibilities can materialize, even if only for a few days, and show the path toward new practices in the fashion system.

How do the academic backgrounds in Design for Made in Italy enhance your ability to address the needs of struggling communities through fashion initiatives?

It is precisely thanks to the activation of the National PhD in Design for Made in Italy that this collaboration became possible. Our research paths find common ground in project-based work, and therefore in the educational process we mentioned earlier. In particular, Andrea Bertello is engaged in research on fashion education in Italy, which stems from the study of materials from the Max Mara Business Library and Archive, a partner co-financing his PhD scholarship. Part of his research involves the patternmaking manual from the Scuola Maramotti, which trained the first Max Mara factory workers, reactivated for this project to test its relevance and inclusivity.

My research, on the other hand, aims to foster an empowerment pathway for the atelier, both commercially and as a project of innovation and valorization of the Scampia territory. Pursuing the objectives of a social tailoring atelier today primarily means ensuring economic sustainability to grow and enrich the offering, not only in terms of products but also in terms of services for the community, dedicated to spreading culture. This involves analyzing what social ateliers are today and how they can function within a broader framework in which diverse actors participate, including industry professionals, suppliers, emerging brands, artists or creatives, associations, universities, academies, museums, and more. We believe that for these realities to function fully, they must weave community relationships on the ground, proposing true innovation that can be accessed from the bottom up.

Our collaboration created space for a conversation that needed to include multiple voices to advance the capsule project in an innovative way. Thanks to the supplies from the historic company Manteco S.p.A., we were able to work with high-quality fabrics that themselves tell a story of attention to textile sustainability. The Tuscan company is highly specialized in sustainable luxury fabrics made from both animal and plant fibers. In particular, they are leaders in fabrics derived from virgin wool and recycled wool (MWool Virgin and MWool Recycled). The wool from their Recycled line provided the foundation for our work. In the atelier, we collectively selected combinations based on weight, color, and patterns.

What aspects of the collection reflect a commitment to uplifting marginalized voices, and how does this engage the audience in meaningful dialogue?

The collection reflects above all a method, a way of being in the territory and building shared visions. It was not born in a studio or an academy, but in a small social atelier that confronts real problems every day — lack of economic autonomy, job insecurity, interrupted life paths, fragile families. What we did was transform this context into project knowledge. The capabilities of the seamstresses, volunteers, and younger girls became not only “contributions,” but the very foundation of the capsule’s identity.

The collection thus incorporates fragments of stories: fabrics chosen together in the workshop, discussions about shapes, exercises to translate into aesthetics what Scampia represents today — not only difficulties, but also creativity, irony, resilience, and the desire for the future.

The aesthetic elements are not decorations, but narrative devices. Trims, textures, and certain garment constructions are connected to an imaginary of the neighborhood that we chose to rethink, decontextualize, and relocate into a contemporary language, in order to remove Scampia from the rhetoric of the “social problem” and bring it into an international dialogue.

For the audience, observing the collection does not offer a folkloric or stereotypical representation, but an invitation to enter complexity. The garments do not speak about the community, but with the community, as they are the result of shared design in which the seamstresses were active protagonists. This makes the dialogue with the viewer much more powerful, as it becomes clear that fashion is not only surface, but a structure capable of narrating deep social dynamics.

How does Virginia Woolf’s idea of a “room of one’s own” serve as a foundational principle for advocating women’s autonomy in the fashion industry, particularly for those from disadvantaged backgrounds?

The reference to Virginia Woolf stems from the need to give the project a conceptual foundation that is not only aesthetic or narrative, but political in the most human and everyday sense of the word. In 1929, Woolf invited the students at Cambridge to claim “a room of one’s own,” a space of freedom, economic autonomy, and expressive independence, without which — she argued — a woman cannot truly create, write, or imagine a life of her own outside social and familial impositions. Nearly a century later, that image remains incredibly relevant.

In marginalized neighborhoods, public housing, and families living with precarity and scarce resources, a “room of one’s own” is not merely a metaphor: it is something that often does not exist at all. Many women live in contexts where there is no space, physical or mental, to recognize themselves, express themselves, make mistakes, or grow. Where time is dictated by duty, care for others, and the urgencies of everyday life.

In our work, Woolf’s imagined room becomes a sewing machine: A Sewing Machine of One’s Own.A humble, common, domestic object, yet incredibly powerful. It is a space that opens up even where a room does not exist. A tool that enables independence, generates value, transforms materials, and, in turn, transforms the maker. In the project, this metaphor becomes concrete: fashion not as luxury, but as possibility. A means to choose freedom every day through small acts of resistance, self-care, and courage. The sewing machine becomes the symbolic space in which to reconstruct one’s identity, one’s time, and one’s story. It is an act of self-determination that belongs to anyone, not just those who work in fashion.

Ultimately, what Woolf asked for was simply this: to find a place to recognize oneself. Our project seeks, in the most respectful way possible, to build a bridge between that idea and today’s marginalized realities, showing that autonomy and creativity can emerge even in the most fragile contexts, and that design can be a catalyst for dignity, opportunity, and a shared future.

In what ways can the metaphor of a sewing machine symbolize not only personal autonomy but also collective empowerment and community healing within the realm of fashion?

The sewing machine is a powerful metaphor because it brings together two dimensions: the individual and the community.

On a personal level, as we mentioned, it is a point of access to freedom: it allows a woman to learn a craft, to see her work transformed into a recognized product, and to imagine a trajectory different from the one the territory often imposes.

At the same time, the atelier is a collective space, and the sewing machine becomes a node of relationships: people help each other, correct one another, share failures and discoveries, and build knowledge that does not belong to a single person but to the group.

This relational dimension is central to the project: co-design, continuous dialogue, rewriting mistakes together, and the care that comes from standing side by side. True healing is not an individual matter; it is a communal process. And it happens when people feel part of something, when work becomes a safe space, when a project becomes a tangible possibility, when a finished garment carries the proof that “I can do it.”

How does the curatorial vision for this project seek to illustrate clothing as a powerful medium for social change, and what concrete examples from the collection demonstrate this vision?

The project’s curation stems from the desire to show how clothing, when designed in a certain way, can become a lens for understanding complex social dynamics. We chose to present the capsule as a process, not as an isolated aesthetic outcome.

The garments are conceived not merely as products, but as material traces of shared work: they mark the steps, choices, doubts, and discussions in the atelier. The way they are constructed, the combination of fabrics from Manteco S.p.A. with trims from San Leucio Design, and the use of details referencing the neighborhood, all aim to show how fashion can unite elements that normally remain separate: centers of excellence and urban peripheries, virtuous supply chains and fragile contexts, historic craftsmanship and neighborhood creativity.

The inclusion of trims takes on an even stronger symbolic value when considering the history of San Leucio, whose silk tradition began in the eighteenth century as an Enlightenment-era social project initiated by Ferdinando IV. The Antico Opificio, with its jacquard, brocade, and damask silks, represents not only a center of excellence in craftsmanship, but also the legacy of a utopian experiment in community, labor, and shared education. It is precisely from these scraps that we created the patchwork dress.

What collaborative strategies does the project implement to ensure that local communities are active participants rather than passive recipients in the fashion process, and why is this model important?

The main strategy is not to “bring” a project to Scampia, but to build it with Scampia. This means:

– sharing design tools with the seamstresses and volunteers;

– including skills and aspirations at every stage of the process;

. creating an ecosystem of diverse actors (companies, universities, artisans, creatives, associations) to achieve a common goal: bringing culture.

This model is important because it dismantles the charity-based logic that often characterizes projects aimed at fragile territories. Here, the community is not a mere recipient, but a co-author. And this is precisely what generates change: people gain confidence, responsibility, and visibility. Fashion, in this way, is not an external intervention, but a shared process capable of circulating skills and opportunities.

How does “A sewing machine of one’s own” challenge conventional understandings of femininity and independence, and what implications does this have for those in communities that face systemic barriers?

The femininity that emerges from A Sewing Machine of One’s Ownis not aesthetic, it is political. It does not speak of delicacy or order, but of clarity, effort, and responsibility that permeate daily life. It is a femininity that does not aim to please, but to convey the strength that comes from doing, from building, from taking a stand through small, concrete actions.

Even independence, in our capsule, is not a pose: it is a collective process. It arises from working together, learning a craft, and seeing one’s contribution publicly recognized. It became particularly clear during the making of the video directed by Michel Liguori. There was no large production, just us, them, and the neighborhood. And precisely because of that, it was significant. We walked together to identify the most iconic locations, and one of the seamstresses spontaneously offered herself as a model, with a naturalness that immediately gave meaning to everything. It was a simple yet intense experience, meaningful for all of us: for them, because they saw themselves in a new role, and for us, because we felt a growing engagement, almost a small awakening of awareness and pride.

This is where the project truly challenges conventional imaginaries: it contests the idea that women in the peripheries are “fragile recipients.” In this project, they become professionals, carriers of imagination, protagonists of their own story. The implications are significant: when a community has access to creative tools and spaces for real expression, new possibilities arise — symbolic, social, and professional. A Sewing Machine of One’s Ownshows that independence is not an abstract ideal, but an ecosystem of relationships, opportunities, and tools capable of transforming one’s perception of oneself and one’s future.

A note to your future self.

To my future self, I would say, never forget what you saw in the atelier, the care hidden in the smallest gestures, the patience of the seamstresses, the irony in difficult moments, the clarity with which they spoke about their lives. Remember that you are not just building a collection, you are imagining a new way of making fashion, one that does not use people but includes them, one that does not aestheticize marginality but transforms it into value.

And when you have doubts, look back at this project and remember that you started from a wooden table, in a place that promised nothing, and from there you built a piece of the future together with them.

Photography: Laura Paltenghi

Video directed by Michel Liguori

Creative Direction & Set Design: The Entire Team

Costume Design: Andrea Bertello & Eleonora Cecere

Styling: Eleonora Cecere

Costume Design: Andrea Bertello & Eleonora Cecere

Models: Naomi Guerra, Martina Pollio, Ciro Lettera

Casting & Location Manager: Teresa Salvatrice

Assistants: Alessia Guerra, Fabiana Balzamo, Melania Arcone, Pasquale Frattini

Independent Production

Textile Partners: Manteco S.p.A.; Antico Opificio Serico, San Leucio Design

Partners of the project:

Fatto@Scampia, Fondazione Città Nuova,

Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli,

National PhD Program in Design for Made in Italy, Università IUAV di Venezia